中文

ENGLISH

中文

ENGLISH

While 3D printing is largely associated with manufacturing and prototyping, it has garnered some attention for its ability to reconstruct, renovate and repair objects as well. This makes it a fairly useful resource for museums, curators and historians looking to reconstruct objects, artifacts and even fossils with the use of printing, scanning and digital models.

Here are a few of the ways additive manufacturing technologies are breathing new life into old artifacts:

Image Credit: 3D Systems

As most people in the know-how are aware, 3D printers have become a major asset in the production of figurines and statuettes. By extension, this same ability to scan and create forms has been a boon to the art and sculpture restoration field. One great example comes from the Great Pagoda at Kew Gardens.

Last year, restorers in association with Historic Royal Palaces (HRP) took on the monumental task of bringing back the glory of the 72 dragon sculptures at the Great Pagoda. These elaborate statues were given a do-over using 3D Systems’ selective laser sintering (SLS) technology. The dragons had been missing for a long time due to wood rot, which needed to be dealt with using the best in modern technologies.

3D Systems’ On Demand Manufacturing team were able to use Geomagic software, their own Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) tech to create lightweight, durable replicas of the original dragons consisting of DuraForm PA. Though these versions were made of differing materials, the restorers were able to produce a look and feel comparable to the original dragons. These new versions were not going to rot away like their predecessors and were also easily reproducible if need be.

However, sculpture restoration can be taken even further…

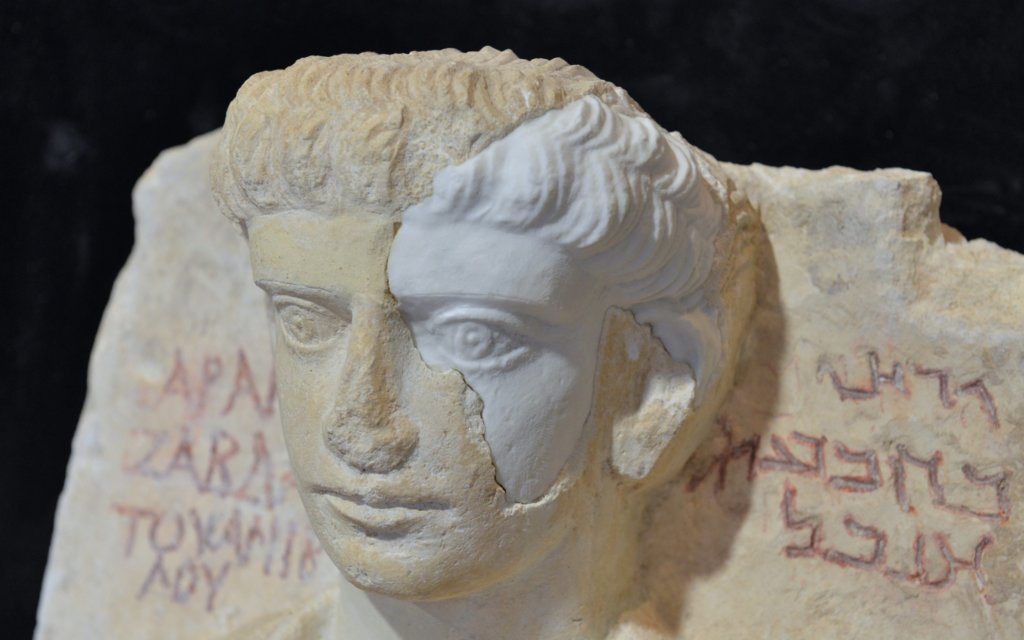

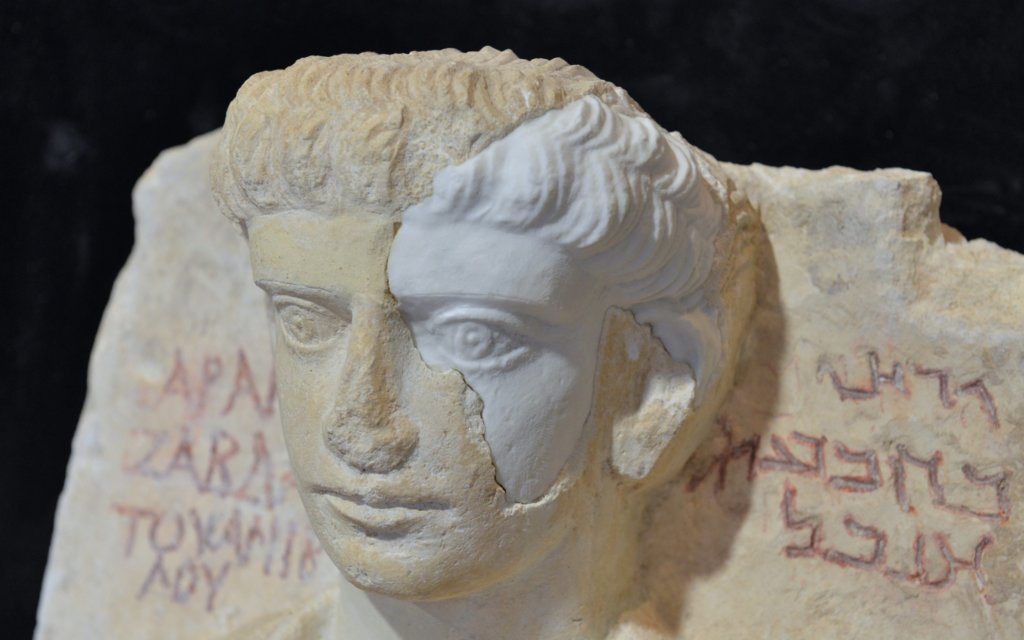

Image Credit: Chris Warde-Jones/ the Telegraph

Even in places as desolate and grief-stricken as Syria, archaeologists and historians are scrambling to preserve human culture. After major attacks on Palmyra, quite a few landmarks and crucial pieces of history had taken some damage. Many artifacts were salvaged from Palmyra’s museums after the site was retaken by Russian and Syrian forces. The damaged works and sculptures were taken to Beirut and then to Rome, where a dedicated team of experts from the Institute for Conservation and Restoration (ICR) began work on bringing them back to their former glory.

Among other restoration projects, technicians used laser scanners to retrieve in-depth structural data and were able to 3D print the missing aspects of statues. One statue was especially badly damaged, losing roughly half of its face, so technicians created a “prosthetic” replacement for the missing portions. The prosthetic was attached to the remainder of the bust with six small magnets, making it easily removable in case the missing pieces are ever retrieved.

A similar project was in need at the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence, Italy. As one of the most prestigious public institutes in the field, it houses some very old works of art. These works are often in need of more extensive care, which is why restorers like Mattia Mercante have been using advanced technologies like 3D printing and 3D scanning to get these works of art and other cultural artifacts back on their feet.

Applying the tools of 3D modeling and digital sculpting, trying to achieve the most faithful reconfiguration possible. “Digital scanning and modeling guarantee greater respect for the original artistic style,” said Mercante. “Restorers are art technicians, not painters or sculptors—the interpretative and creative aspects shouldn’t influence our work.”

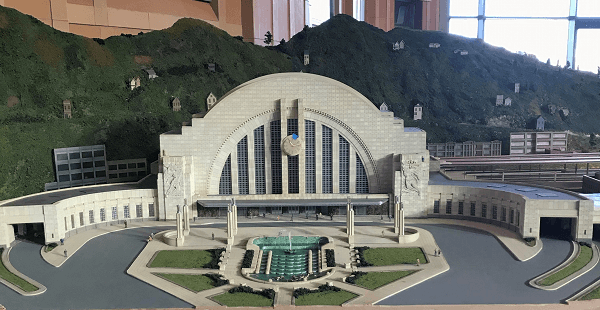

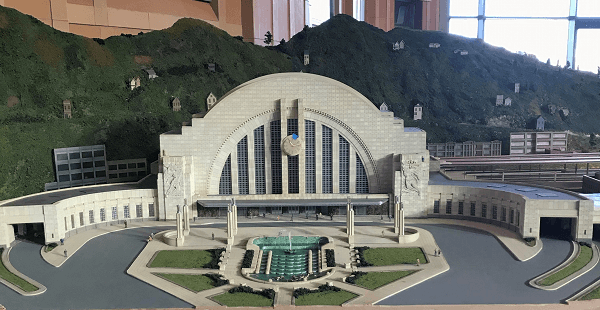

Recreating buildings and models has always been a major draw of 3D printing, so it’s no wonder that museums are starting to tap into this potential for large-scale exhibits. With the aid of 3D printing the Cincinnati Museum Center reconstructed an S-scale model of the downtown area of the city as it stood in the 1940s, complete with Carew Tower, City Hall, Plum Street Temple, the Roebling Bridge and streetcars rattling through the streets.

The realistic recreation features familiar sights, sounds and smells even, portraying an older vision of the city’s history and culture. The impressive recreation used a mix of many manufacturing technologies to create a 4,000-square-foot display. The total exhibit features more than 1,200 buildings, 18 running locomotives, four operational inclines, over 500 vehicles and 2,000 people.

The display is not yet complete and is still expanding in size and scope. It offers a lot of insight into the architecture and history of the past while creating an immersive, physical experience for any visitors to the museum.

Image Credit: Dušan Hein, TASR (Slovak Uprising Museum)

Museums all around the world are putting a lot of effort into digitization and 3D models due to how they can allow them to complete and reattach fossil parts using printed components. Fossils are hard enough to find on their own, but finding one preserved in proper shape is nearly impossible. In these cases, a little bit of ingenuity goes a long way to giving visitors to museums the full picture.

The Slovak Uprising Museum (SNP) and the Smithsonian have employed such projects to great effect. Dinosaur fossils are a crucial part of any museum but these bones can be severely damaged or have crucial joints in severe need of support. This is where 3D printers come in and give educators and paleontologists the tools to improve these displays.

But dinosaur bones aren’t the only ways in which history is being revived. Scientists used 3D scans to map a mummy’s entire vocal tract, using such models to recreate the vocal organs using a 3D printer. This artificial larynx can run air through the synthetic vocal cords, creating a single vowel sound in the dead Egyptian’s voice, according to findings published in the journal Scientific Reports.

The vocal organs in question once belonged to a priest who lived in Thebes during the tumultuous reign of Rameses XI. The mummified corpse was initially recovered about 200 years ago and sold to a museum in the United Kingdom, where it was unwrapped and dubbed the Leeds Mummy. Now, researchers are using it as the basis for this sort of experimental research. Though the tract can only utter singular vowel sounds, it’s an astonishing achievement.

In these ways, they are allowing us to reinvigorate the study of history and provide us with a better understanding of the past with futuristic technologies.

While 3D printing is largely associated with manufacturing and prototyping, it has garnered some attention for its ability to reconstruct, renovate and repair objects as well. This makes it a fairly useful resource for museums, curators and historians looking to reconstruct objects, artifacts and even fossils with the use of printing, scanning and digital models.

Here are a few of the ways additive manufacturing technologies are breathing new life into old artifacts:

Image Credit: 3D Systems

As most people in the know-how are aware, 3D printers have become a major asset in the production of figurines and statuettes. By extension, this same ability to scan and create forms has been a boon to the art and sculpture restoration field. One great example comes from the Great Pagoda at Kew Gardens.

Last year, restorers in association with Historic Royal Palaces (HRP) took on the monumental task of bringing back the glory of the 72 dragon sculptures at the Great Pagoda. These elaborate statues were given a do-over using 3D Systems’ selective laser sintering (SLS) technology. The dragons had been missing for a long time due to wood rot, which needed to be dealt with using the best in modern technologies.

3D Systems’ On Demand Manufacturing team were able to use Geomagic software, their own Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) tech to create lightweight, durable replicas of the original dragons consisting of DuraForm PA. Though these versions were made of differing materials, the restorers were able to produce a look and feel comparable to the original dragons. These new versions were not going to rot away like their predecessors and were also easily reproducible if need be.

However, sculpture restoration can be taken even further…

Image Credit: Chris Warde-Jones/ the Telegraph

Even in places as desolate and grief-stricken as Syria, archaeologists and historians are scrambling to preserve human culture. After major attacks on Palmyra, quite a few landmarks and crucial pieces of history had taken some damage. Many artifacts were salvaged from Palmyra’s museums after the site was retaken by Russian and Syrian forces. The damaged works and sculptures were taken to Beirut and then to Rome, where a dedicated team of experts from the Institute for Conservation and Restoration (ICR) began work on bringing them back to their former glory.

Among other restoration projects, technicians used laser scanners to retrieve in-depth structural data and were able to 3D print the missing aspects of statues. One statue was especially badly damaged, losing roughly half of its face, so technicians created a “prosthetic” replacement for the missing portions. The prosthetic was attached to the remainder of the bust with six small magnets, making it easily removable in case the missing pieces are ever retrieved.

A similar project was in need at the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence, Italy. As one of the most prestigious public institutes in the field, it houses some very old works of art. These works are often in need of more extensive care, which is why restorers like Mattia Mercante have been using advanced technologies like 3D printing and 3D scanning to get these works of art and other cultural artifacts back on their feet.

Applying the tools of 3D modeling and digital sculpting, trying to achieve the most faithful reconfiguration possible. “Digital scanning and modeling guarantee greater respect for the original artistic style,” said Mercante. “Restorers are art technicians, not painters or sculptors—the interpretative and creative aspects shouldn’t influence our work.”

Recreating buildings and models has always been a major draw of 3D printing, so it’s no wonder that museums are starting to tap into this potential for large-scale exhibits. With the aid of 3D printing the Cincinnati Museum Center reconstructed an S-scale model of the downtown area of the city as it stood in the 1940s, complete with Carew Tower, City Hall, Plum Street Temple, the Roebling Bridge and streetcars rattling through the streets.

The realistic recreation features familiar sights, sounds and smells even, portraying an older vision of the city’s history and culture. The impressive recreation used a mix of many manufacturing technologies to create a 4,000-square-foot display. The total exhibit features more than 1,200 buildings, 18 running locomotives, four operational inclines, over 500 vehicles and 2,000 people.

The display is not yet complete and is still expanding in size and scope. It offers a lot of insight into the architecture and history of the past while creating an immersive, physical experience for any visitors to the museum.

Image Credit: Dušan Hein, TASR (Slovak Uprising Museum)

Museums all around the world are putting a lot of effort into digitization and 3D models due to how they can allow them to complete and reattach fossil parts using printed components. Fossils are hard enough to find on their own, but finding one preserved in proper shape is nearly impossible. In these cases, a little bit of ingenuity goes a long way to giving visitors to museums the full picture.

The Slovak Uprising Museum (SNP) and the Smithsonian have employed such projects to great effect. Dinosaur fossils are a crucial part of any museum but these bones can be severely damaged or have crucial joints in severe need of support. This is where 3D printers come in and give educators and paleontologists the tools to improve these displays.

But dinosaur bones aren’t the only ways in which history is being revived. Scientists used 3D scans to map a mummy’s entire vocal tract, using such models to recreate the vocal organs using a 3D printer. This artificial larynx can run air through the synthetic vocal cords, creating a single vowel sound in the dead Egyptian’s voice, according to findings published in the journal Scientific Reports.

The vocal organs in question once belonged to a priest who lived in Thebes during the tumultuous reign of Rameses XI. The mummified corpse was initially recovered about 200 years ago and sold to a museum in the United Kingdom, where it was unwrapped and dubbed the Leeds Mummy. Now, researchers are using it as the basis for this sort of experimental research. Though the tract can only utter singular vowel sounds, it’s an astonishing achievement.

In these ways, they are allowing us to reinvigorate the study of history and provide us with a better understanding of the past with futuristic technologies.